The Edict of Milan (313 CE)

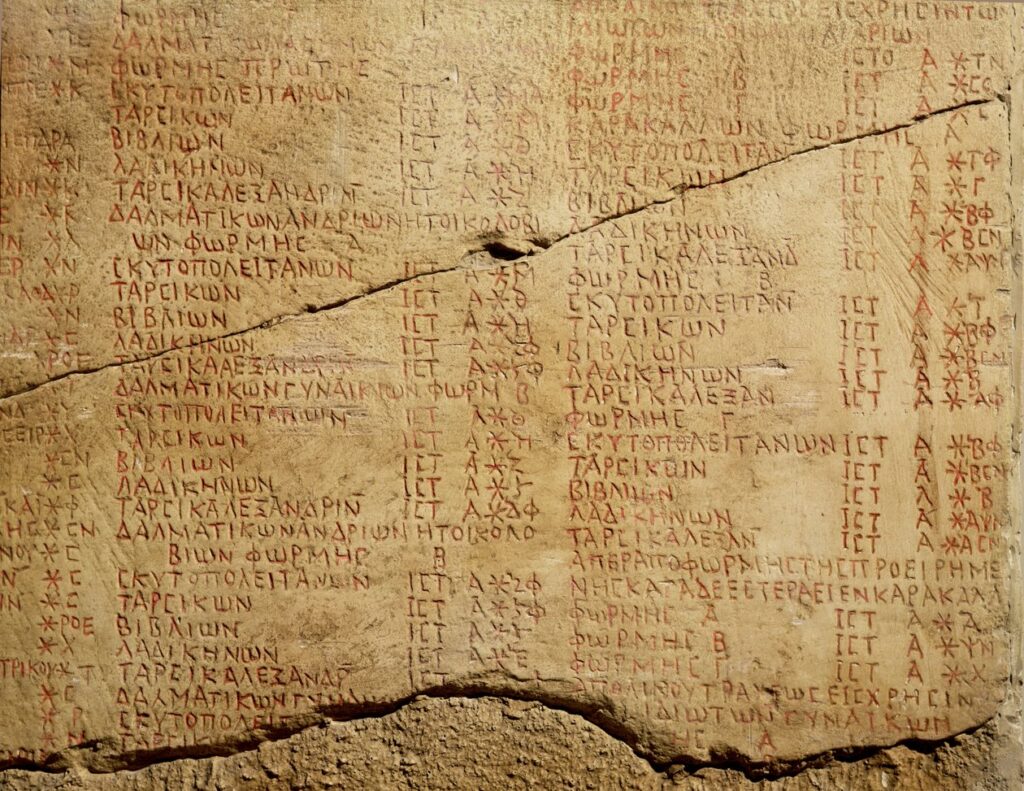

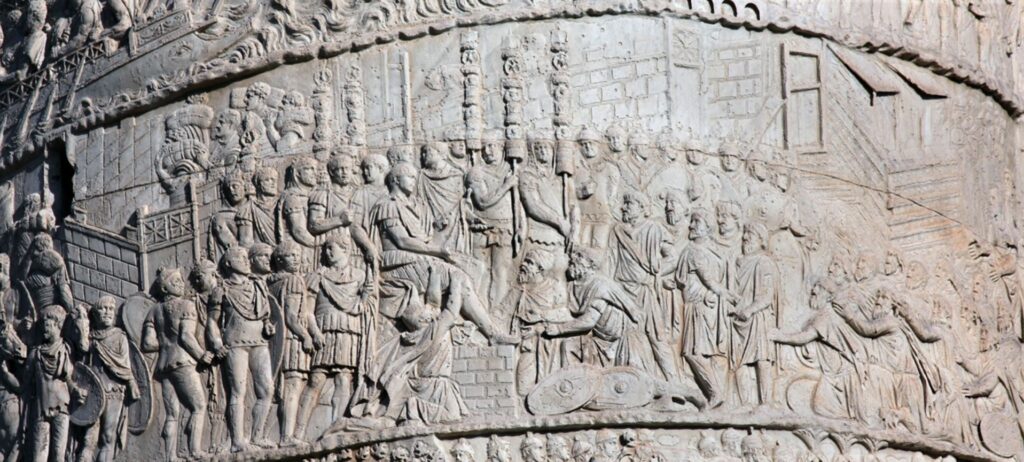

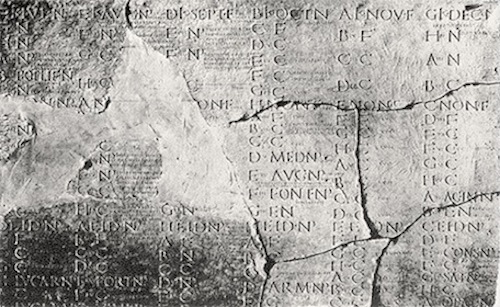

The Edict of Milan, issued in 313 CE by Emperors Constantine I and Licinius, marked a turning point in religious history. By giving everyone the freedom to worship whichever god they choose, it put an official stop to the persecution of Christians. Most significantly, it recognized Christianity as a legitimate religion, allowing Christians to worship openly, build churches, and reclaim property that had been confiscated during earlier periods of repression. This edict was essential to the quick spread of Christianity and established the foundation for religious liberty in the Roman Empire. Historical significance The edict dramatically changed the status of Christianity. Before the Edict, Christianity was forbidden and Christians often faced persecution. The Edict of Milan officially legalized Christianity, allowing its followers to worship without fear of punishment. The edict ordered that property taken from Christians during earlier persecutions be returned. This was a major shift in imperial policy and marked the beginning of Christianity’s transformation into a dominant religion in the Roman Empire and later Europe, deeply influencing Western culture, art, politics, and law. Cause and consequence Before the Edict of Milan in 313 CE, Christianity was strictly forbidden and subject to severe persecution. Roman rulers insisted that people worship the traditional Pagan gods in order to secure divine protection during times of economic instability and military defeat. Emperor Diocletian began the most severe campaign against anyone who refused to offer sacrifices to the Roman gods in 303 CE, known as the Great Persecution. Mass executions and church destruction resulted from Christians’ refusal to worship any other deity than their own, which was viewed as treason. With Emperor Galerius’ Edict of Toleration in 311 CE, persecution started to lessen. A turning point came in 312 CE when Constantine I reportedly had a vision of the Christian symbol (Chi-Rho) before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge and credited his victory to the Christian God. He adopted tolerance as a means of unifying and stabilizing the empire in the face of growing instability and a rapidly increasing Christian population.With the Edict of Milan, Christians experienced a significant change in their freedom to construct churches, worship freely, and recover property that had been taken from them. It also allowed everyone to practice their religion freely, promoting tolerance and diversity in society. In the decades that followed, Christianity grew quickly, and in 380 CE, Emperor Theodosius I issued the Edict of Thessalonica, establishing Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire. By the late 4th and early 5th centuries, Christianity had been fully assimilated into Roman politics and culture, while pagan practices had gradually diminished. Continuity and change Roman politics had always been heavily influenced by religion, as evidenced by the reverence for traditional Roman gods and emperor worship. The Edict of Milan continued this tradition, but with Emperor Constantine I’s support, it shifted the focus to Christianity. Although the Edict encouraged tolerance, as Christianity grew in power, tensions between various religious groups, particularly Christians and pagans groups, increased. Previously forbidden and persecuted, Christianity was now lawfully recognized. It allowed Christians to own property, construct churches, and practice freely. For the first time in Roman history, everyone was legally allowed to worship the religion of their choice, marking a significant shift from earlier laws that favored Roman pagan gods and persecuted other beliefs. The Edict allowed the Christian Religion to become more organized, visible, and politically powerful, setting the stage for its future dominance in Europe. Historical perspective For those who lived in the Roman Empire in 313 CE, the Edict of Milan would have indicated a dramatic and unexpected shift in imperial policy. After years of cruel and violent persecution, the edict was viewed by Christians as a sign of divine favor and a miraculous change. Roman rulers Constantine and Licinius viewed the edict as a strategic step to stabilize a divided and diverse empire. They tried to gain control over Christians and lessen the turmoil caused by conflicts over religion by promoting religious tolerance. The edict also stated that all religions should be accepted, so it did not just help Christians. Given the growing influence of Christianity, the edict may have caused confusion or anxiety among traditional pagans. Historians view the Edict of Milan as a turning point in the evolution of religious freedom and tolerance. The ruins of the Emperor’s palace where Constantine and Licinius issued the Edict of Milan, Mediolanum, Milan (Italy) Video

The Edict of Milan (313 CE) Read More »