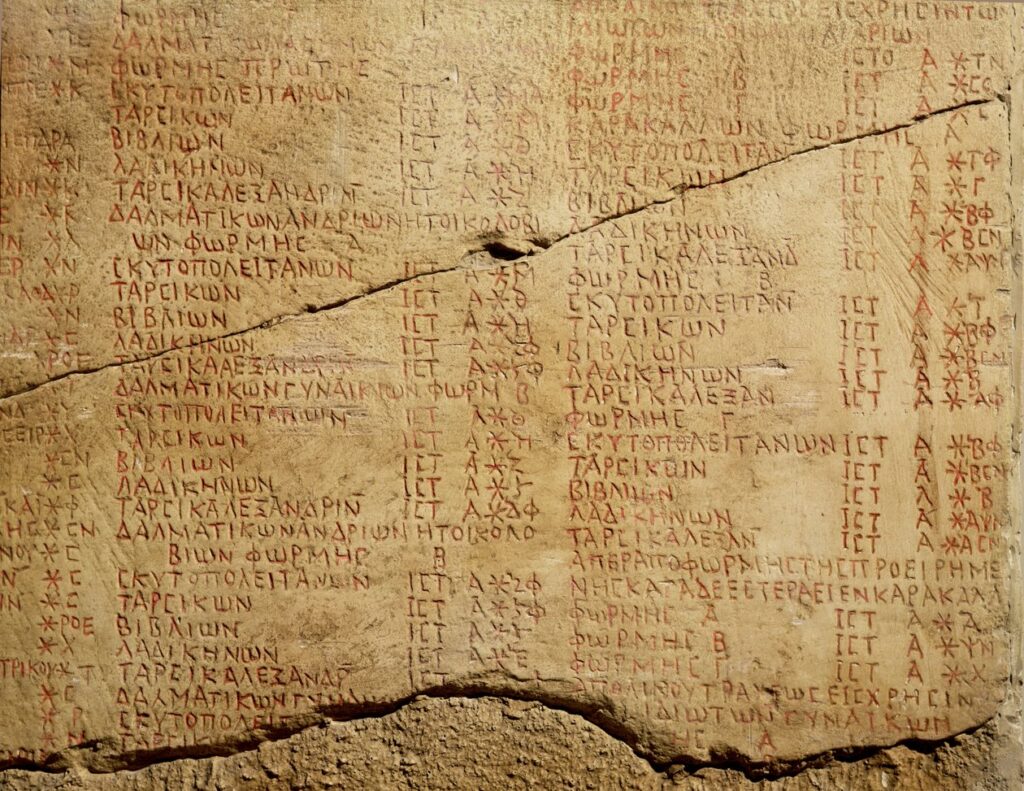

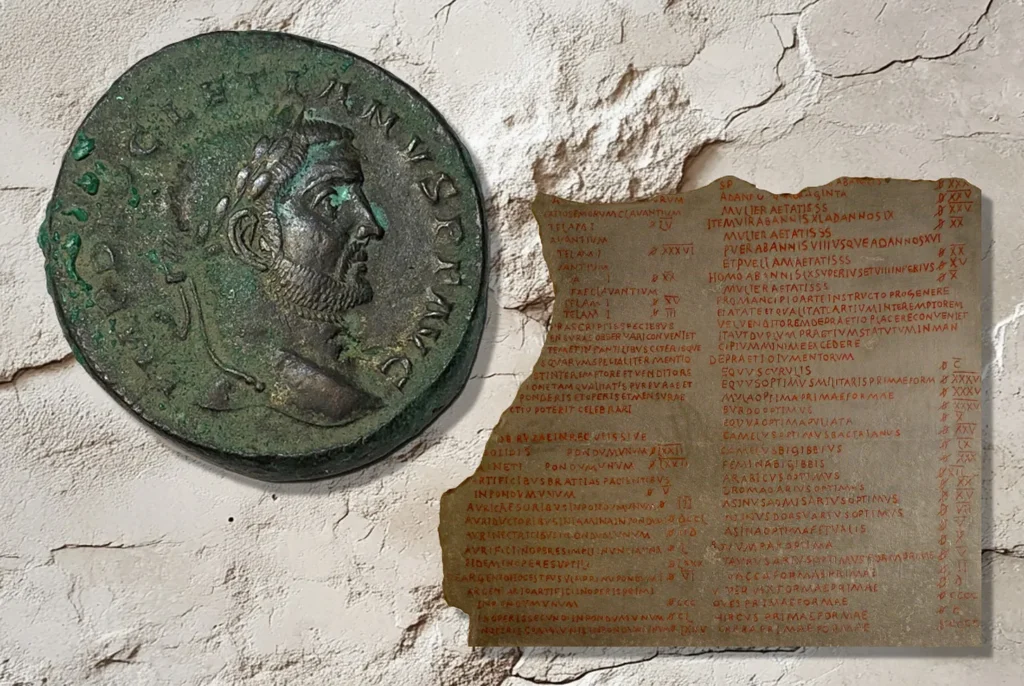

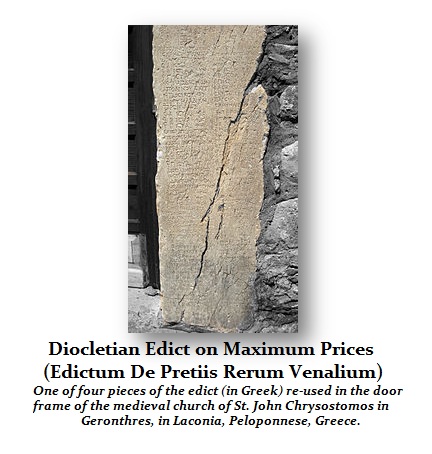

The Edict on Maximum Prices, issued by Emperor Diocletian in 301 CE, was one of the most ambitious economic measures in Roman history. It aimed to control soaring inflation and stabilize the Roman economy. The law sets maximum price limits for more than 1.200 products, raw materials, labour and services, transport, animals and even slaves. It was inscribed on stone tablets and distributed throughout the empire. Violators faced severe punishments, including the possibility of execution.

Connection to the Decline of the Roman Empire

The Edict of Maximum Prices aimed for economic stabilization but instead deepened existing economic issues. The Edict led to market shortages since merchants declined to sell their goods at the enforced low prices, which caused both scarcity and economic stagnation rather than stabilizing prices. The empire’s inability to compensate its soldiers resulted in diminished state power and undermined public confidence in the government. The enforcement of set prices created corruption and illegal trading networks while restrictions on wages caused workers to leave their jobs, making labor shortages more severe

Continuity and change

The Edict of Maximum Prices demonstrated Rome’s economic interventionism as a continuation. Rome had a long history of state control over economic affairs, such as the Annona system, a state-controlled grain supply system, which included measures to regulate prices, prevent hoarding, and ensure fair distribution. The principal reason for the official overvaluation of the currency, of course, was to provide the wherewithal to support the large army and massive bureaucracy. Roman elites traditionally resisted substantial economic reforms and focused on temporary fixes through tax hikes and currency debasement. The Edict marked a shift toward harsher economic policies, enforcing rigid price controls and severe penalties.

Positive and negative consequences

The enforcement of the Edict of Maximum Prices brought mostly negative consequences because it failed to stop inflation while making shortages more severe. It further eroded trust in the government and revealed its failure to handle the crisis. The desperation of Rome’s leaders was evident because they chose extreme actions to postpone their downfall instead of tackling the fundamental problems.

How Rapid Were These Changes?

For decades, the Roman economy steadily declined due to persistent inflation, heavy taxation, and widespread corruption. The Crisis of the Third Century played a major role in the collapse of the empire’s economy by causing widespread disruption. Economic difficulties that were once localized and manageable had, by 301 CE, spread across the entire empire and became extremely difficult to reverse. Although Rome did not fall immediately, the economic turmoil of the late third and early fourth centuries marked a decisive turning point toward irreversible decline.

A turning point

While price-fixing was not new, the Edict of Maximum Prices marked an unprecedented level of state intervention, signaling that Rome’s problems had reached a critical point. The Edict of Maximum Prices ultimately failed as an authoritarian attempt to curb inflation, and, along with the introduction of the Tetrarchy, a system created by Diocletian in which four rulers shared power, it led to more chaos and decline in the empire.